Corporate Periodization, INCS conference preview

The Interdisciplinary Nineteenth Century Studies conference is March 10-13, in Asheville, NC, and I’ll be presenting part of my current book project about the Victorians and the Walt Disney Company. The paper argues that literary and corporate periodization are analogous, each stemming from particular institutional objectives, and demonstrates the analogy by examining the history of the Walt Disney Company.

In fitting the paper to its necessary length I wrote two sections that don’t fit exactly into the argument, and I decided to post them here as a preview of (or complement to) the paper. The first part explores the imagined contrast between making art and making money. The second very briefly identifies different periods in the management of the Lyceum Theater, which I see as a historical example of the kind of periodization I’m claiming for Disney.

Making Art and Making Money

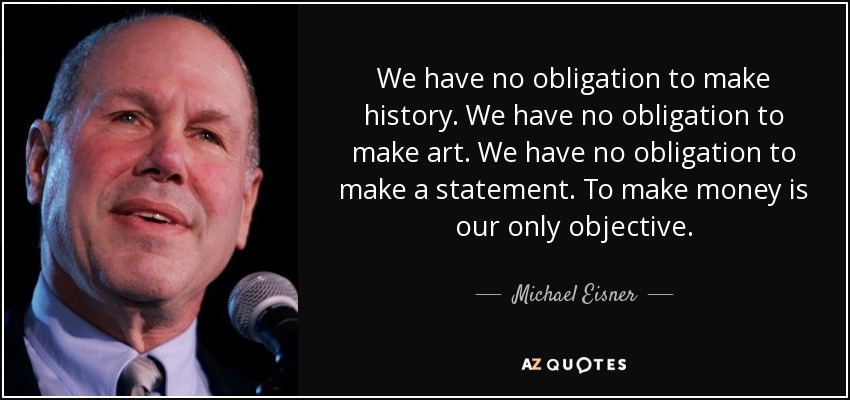

The imagined corporate ethos is encapsulated in an internal memo written by Michael Eisner, CEO of the Walt Disney Company from 1984 to 2005. The memo is famous enough that it has become a meme:

I first encountered this memo in Henry Giroux’s The Mouse That Roared. Giroux argues that Disney is a cultural icon, but its profit-centered motivation makes it a threat to Democratic values (Giroux 25). For those who value making art, history, and statements over making money, Eisner’s memo raises eyebrows. And it’s easy to imagine a corporate executive spouting claims like this. It’s a too-perfect encapsulation of the neoliberal values we fear are encroaching into the university.

But the next sentence of the memo changes things a bit, at least for me. And it tends to be left out of the memes. Here is the slightly extended version:

We have no obligation to make art. We have no obligation to make history. We have no obligation to make a statement. But to make money, it is often important to make history, to make art, to make some significant statement. (Stewart 23; Eisner)

Eisner is a corporate CEO, and clear about his priorities. But he is also aware of the kind of company he’s leading. In his 1998 memoir he doubles down on the idea, and claims to be riffing on Woody Allen’s claim that “if show business weren’t a business, it would have been called ‘show show’” (Eisner).

It’s the contrast between these different values that interests me most, and the way they are too often framed as a zero-sum game. Professors are often caricatured as being out of touch, as if our only objective is to teach students and produce research. And I don’t necessarily disagree that that is our objective as faculty. But imagine a university president adapting Eisner’s words:

We have no obligation to make money. To make art, to study history, to make statements is our only objective. But to make art, study history, and make significant statements it is sometimes necessary to make money.

I don’t think that statement is a slippery slope that leads all universities to become like Corinthian Colleges. To insist on a contrast between universities and corporations is to insist on different priorities. It doesn’t mean we remove ourselves entirely from the financial system. When we push for state or federal funding, for student loan reform, for alumni donations, or for higher wages for contingent faculty, we recognize that universities do need to be funded. My paper takes seriously the shared motivations among academics, artists, and corporations.

The Lyceum Theater

The division between corporate and academic ethos is less stark than news coverage makes it out to be. But it nonetheless exists, and does affect the moves we make in our own scholarship. In her book on Gilbert and Sullivan, for example, Carolyn Williams argues that

Genre formation is not only an aesthetic and historical, but also an economic, process, and genre was important to Gilbert and Sullivan’s effort to carve out their own market niche. They distinguished their productions from other theatrical fare through their genre parody and their particular treatments of gender. Their success at capital accumulation supported unusually high production values, which led, in turn, to further capital growth. (Williams 5)

That’s an insightful point, recognizing the link between profit and aesthetics. Williams then emphasizes that capital accumulation “does not reduce the aesthetic dimension of their success” (6). Even when acknowledging the link, she recognizes the need to guard against a backlash that would insist on a divide between art and the marketplace. In arguing that English departments and the Walt Disney Company follow similar institutional drives to periodize, I aim to further bridge that divide.

Theater scholars tend to be especially attuned to financial questions: Williams is just one example, and Shakespeare critics have long been invested in learning about his financial involvement in his companies. For my purposes, the Lyceum Theatre provides an index to theatrical trends, and its operational history demonstrates how an institutional brand can turn a profit by keeping up with the rhythms of popular culture. Built by the Society of Artists in 1772, the Lyceum hosted a variety of exhibitions in the late eighteenth century, including “astronomical demonstrations, air balloons, waxworks, ‘philosophical fireworks,’ boxing matches, circuses, programs of humorous recitations, and concerts” (Altick 54). The site took advantage of fads like waxworks and tableaux vivants as they emerged: Madame Tussaud began her British career at the Lyceum in 1802 (Altick 333) and William Dimond’s The Peasant Boy (1811) featured one of the earliest tableaux (Altick 342).

After hosting operas and fairy extravaganzas around mid-century, the Lyceum later came to be associated with Henry Irving, and especially with Shakespeare: Irving’s 1874 Hamlet has been called “one of the most influential and talked about theatrical roles in the latter part of the nineteenth century” (Young 3). As these examples demonstrate, the Lyceum shifted its strategy to keep up with popular culture, its different stages analogous to literary periods. Today, I would suggest, the Lyceum continues its Victorian legacy: since 1999 it has hosted Disney’s The Lion King, an adaptation of Hamlet that takes combines two distinct trends of twentieth-century pop culture: the animated musical and the Broadway musical.

In the INCS paper, and in the book towards which these arguments are building, I continue developing these analogies to explore how a global media corporation can helps us understand Victorian culture and its reception.

Works Cited

[zotpress items=”PBZP8M7I,U2VGKRX5,4Q25DJ2T,A8464U6X,PRN6PAWW,SVTMN8F5″ style=”modern-language-association” sortby=”author” sort=”ASC”]